Why Your Daughter Keeps Tweaking Her Hamstring

By Emily Neff (Pappas), Ph.D. (c)

Hamstring tweaks are a frustratingly common issue in young female athletes.

If your daughter frequently experiences hamstring strains, there’s likely a deeper reason behind it. Understanding these causes can help prevent future injuries and improve athletic performance.

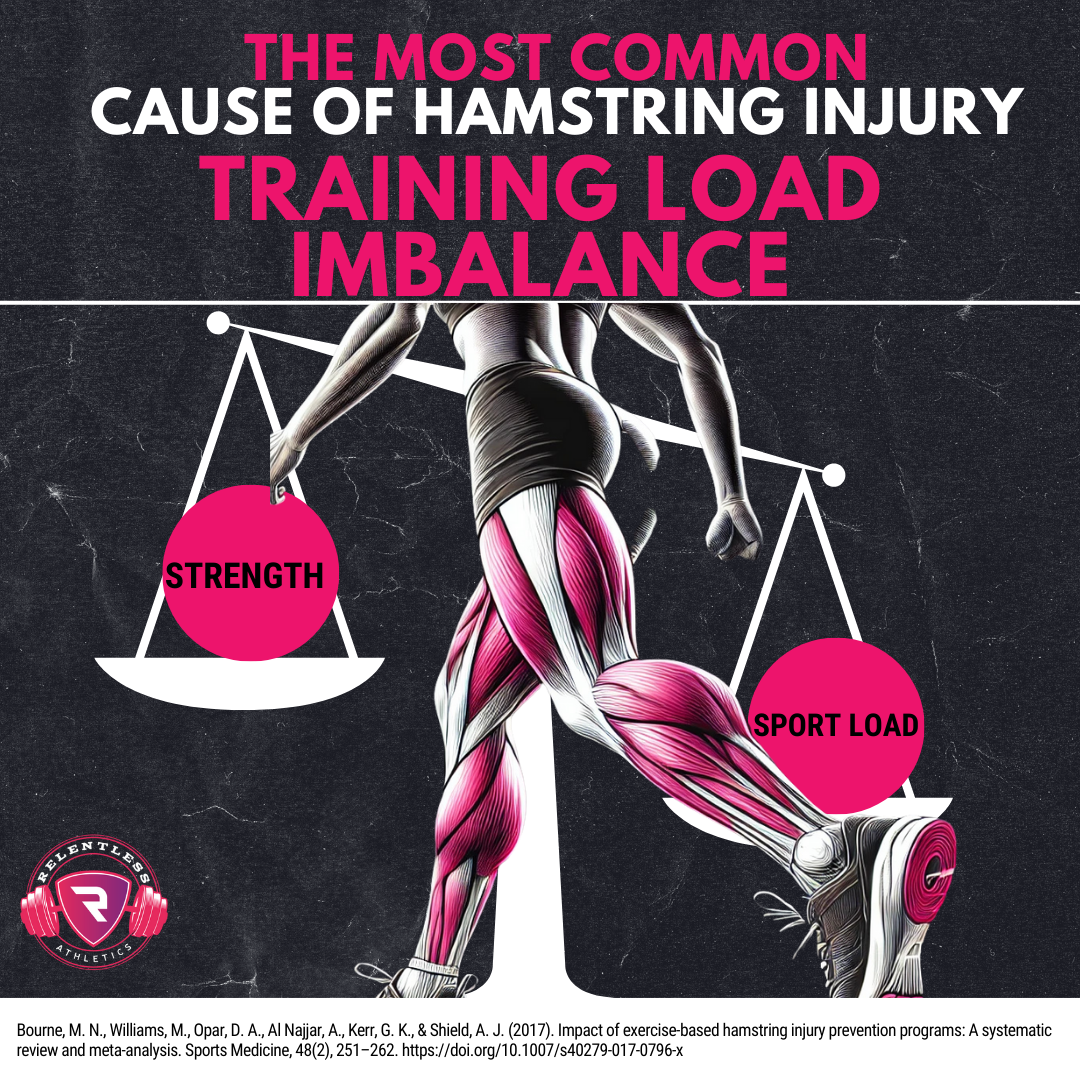

THE MOST COMMON CAUSE: TRAINING LOAD IMBALANCE

The leading cause of recurring hamstring injuries is a mismatch between an athlete's hamstring strength and the workload being placed on those muscles.

If the hamstrings are not strong enough to handle the intensity and frequency of training or competition, they become overworked and prone to strain (Bourne et al., 2017).

WHY ARE FEMALES AT GREATER RISK?

Female athletes are often at higher risk for hamstring injuries due to specific physiological factors:

Type II Muscle Fiber Deficiency

Females tend to have fewer Type II muscle fibers than males. These fast-twitch fibers are critical for rapid force production and absorption, which are essential in sports requiring quick sprints, changes in direction, and jumps.Without sufficient fast-twitch fiber strength, the hamstrings are less equipped to handle high-intensity demands, increasing the risk of injury (Hamada et al., 2000).

Insufficient Strength Training

Many female athletes lack exposure to structured, progressive strength training that develops the hamstring and surrounding muscle groups.Without adequate strength training, muscles struggle to produce and absorb forces safely, leaving the hamstrings vulnerable (Freeman et al., 2021).

OTHER CONTRIBUTING FACTORS

Fatigue and overuse

High training volumes or back-to-back competitions without proper recovery (or inadequate preparation) can leave the hamstrings too fatigued to perform at their peak.Poor Sprinting or JUmping Mechanics

Suboptimal running form, such as overstriding or limited pelvic control, increases strain on the hamstrings during explosive movements (Schuermans et al., 2017).Similarly, poor jumping and landing mechanics can contribute to hamstring injuries, especially when athletes lack the strength to maintain proper joint alignment during high-impact activities.

Research shows that athletes with inefficient landing strategies, such as excessive knee valgus or stiff landings, experience higher forces transmitted through the hamstrings and lower extremities, increasing injury risk (Hewett et al., 2005).

These mechanics are less about "finding the perfect position" and more about ensuring the athlete is strong enough in those positions to handle repetitive impact. Strength drives efficient movement, reducing the need for overcoaching static positions that may not translate to dynamic athletic environments (Kibler et al., 1992).

REDUCED MOBILITY DUE TO WEAKNESS

What appears to be “tight hamstrings” is often a limitation in mobility caused by weakness in the hamstrings, glutes, and core rather than actual muscle shortness (Goom et al., 2016). When muscles are weak, they restrict movement to protect against overstretching, limiting mobility and increasing injury risk.

CONCLUSION

By addressing training load imbalances, sprinting and jumping mechanics, and incorporating targeted strength training, young female athletes can build the resilience needed to avoid recurring hamstring tweaks and stay strong throughout their athletic careers.

REFERENCES

Bourne, M. N., Williams, M., Opar, D. A., Al Najjar, A., Kerr, G. K., & Shield, A. J. (2017). Impact of exercise-based hamstring injury prevention programs: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 48(2), 251–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-017-0796-x

Freeman, S., Patel, A., Gray, D., & Tiller, N. (2021). The importance of strength training in female athletes. Strength and Conditioning Journal, 43(2), 56–64.

Goom, T. S. H., Malliaras, P., Reiman, M. P., & Purdam, C. R. (2016). Proximal hamstring tendinopathy: Clinical aspects of assessment and management. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 46(6), 483–493. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2016.5986

Hamada, T., Sale, D. G., & MacDougall, J. D. (2000). Postactivation potentiation in endurance-trained and strength-trained individuals. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 32(2), 403–411.

Hewett, T. E., Ford, K. R., & Myer, G. D. (2005). Reducing knee and hamstring injuries in female athletes. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 33(4), 492–501.

Kibler, W. B., Chandler, T. J., & Stracener, E. S. (1992). Musculoskeletal adaptations and injuries due to overtraining. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, 20, 99–126.

Schuermans, J., Van Tiggelen, D., Danneels, L., & Witvrouw, E. (2017). Biceps femoris and risk of hamstring strain injury. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 49(1), 22–31.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

In 2015 Emily opened Relentless Athletics to build a community for female athletes while educating their parents and coaches on the necessity of strength training and sports nutrition to optimize sports performance and reduce injury risks in the female athlete population.

Emily holds a M.S. in Exercise Physiology from Temple University and a B.S. in Biological Sciences from Drexel University. She is currently pursuing her Ph.D. at Concordia University St. Paul with a research focus on female athletes & the relationship between strength training frequency, ACL injury rates, and menstrual cycle irregularities (RED-s). Through this education, Emily values her ability to coach athletes and develop strength coaches with a perspective that is grounded in biochemistry and human physiology.

When she isn’t on the coaching floor or working in her office, she is at home with her husband Jarrod and their daughter Maya Rose, and, of course, their dog Milo (who has become the mascot of Relentless)!!