The Most Effective Recovery Modalities for Female Athletes

By Emily Pappas, MS

Fatigue is a necessary response to training that helps stimulate the body to adapt and improve its fitness. Fatigue accumulated over time also is detrimental to performance and results in a degradation of sport outcomes.

The balance between recovery and fatigue is necessary to help enhance adaptive processes, improve performance, and reduce injury risks

However, not all recovery modalities have the same long term outcomes in regards to adaptation and fatigue management.

This article aims to help coaches, parents, and athletes understand the role fatigue plays in athletic performance, the role of recovery modalities, and how their implementation should DIFFER during periods of TRAINING and COMPETITION.

Balancing FATIGUE & RECOVERY for athletic performance

Fatigue- both physiological and psychological- generated during training and competition can greatly reduce an athlete’s sport specific performance capacity.

Despite this performance decrement, it is essential to understand WHY fatigue is generated and its role in the adaptation process.

For both male and female athletes, fatigue is a necessary response to training- where soreness, swelling, and stiffness are elicited by the body to help promote the recovery and ADAPTATION process.

During training periods, the fatigue experienced is necessary to help promote adaptation and future improvements in performance. However, during competition, this fatigue can greatly alter an athlete’s ability to perform.

In order to enhance performance during competition periods and to promote the adaptive potential of an athlete during training periods, recovery modalities must be implemented in proportion to the level of fatigue experienced.

However, current research (1) demonstrates a difference in the long term outcomes of these modalities.

As coaches, parents, and athletes it is essential to understand the role fatigue plays in athletic performance, the role of recovery modalities, and how their implementation should DIFFER during periods of TRAINING and COMPETITION.

Lets dive in:

The Role of Fatigue in Adaptation

When an athlete trains in the gym or on the field, her body experiences stress. This stress is necessary as it provides the needed stimulus to the body to recover and ADAPT or improve its capacity to handle that stress again in the future.

Fatigue is a complex phenomenon resulting from central nervous system, neuromuscular, endocrine, metabolic, and micro-traumatic factors which result in increased physiological responses and perceived effort along with decreased performance indicators (5).

Fatigue is a component of stress and is not inherently “bad”.

The fatigue experienced by an athlete will relate to the type of training performed.

FATIGUE from sport can come from various areas including (1,4,5):

Volume loads from strength training

Distances or durations of conditioning activities

Technical and tactical components of sport training

Physical contacts (tackles, takedowns, etc)

Flexibility and mobility work

Speed and agility training

And competitions (inducing both physical and psychological fatigue)

When the body experiences TOO much fatigue, there will be a decrement in performance.

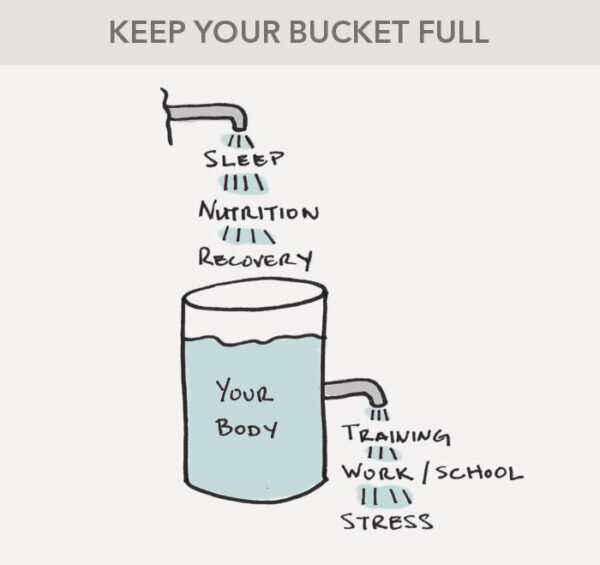

Think of it this way…..

If an athlete performs a highly voluminous lifting session and is unable to recover adequately before her next day sprint practice, her legs will feel heavy and her performance will decrease.

However, this lifting session is paramount to the athlete stimulating her leg muscles to rebuild and produce more force, leading to future faster sprints

In this way fatigue both CREATES and MASKS fitness.

Fatigue is a necessary component of functional overreaching- where an athlete trains VERY HARD to create a stimulus in the body, forcing it to ADAPT and increase fitness overtime.

However, this adaptation does not occur without recovery.

For this reason, achieving an appropriate balance between stress and recovery is an important concept in maximizing the performance of athletes (4).

Fatigue must be MANAGED via training volume and intensity to allow for the “supercomensatory enhancement in performance” (2).

This means an athlete must DECREASE fatigue during important periods of her training to allow her body to RECOVER and adapt to the stimulus created by hard training.

When the body experiences too much fatigue and not enough recovery- breakdown occurs. If this breakdown is chronic, overtime the athlete’s performance will decrease, and potentially never return to its previous level (2).

However, if an athlete doses training with appropriate recovery modalities, her body will ADAPT and improve.

Fatigue is therefore necessary to ENHANCE FITNESS. However these enhancements are not indefinite. Rather, an athlete must continuously train to stimulate her body to MAINTAIN these adaptations. If she wants to adapt even more, she must train HARDER and recover to stimulate an improvement in performance (2,4,5)

During competition periods, fatigue must be MANAGED and reduced in order to express this fitness that has been built in previous training phases. Remember, fatigue masks fitness-- and if an athlete is performing a HARD practice session before her game the next day, her body may not have enough time to recover and therefore her performance in competition will be reduced.

When an athlete is experiencing an imbalance of fatigue and recovery during competition tie, it is common for her to experience (5):

Decrease in technical coordination, resulting in an inability to perform technical skills at the level they were once previously performed - indicating fatigue of the nervous system

Decrease in movement velocity from previous performances in movements like sprinting, throwing, hitting, or barbell movements

INCREASED perception of effort accompanied by POORER performance compared to previous efforts

Decreased desire to train

MOOD disturbances such as restlessness, irritability, and overly emotional

Appetite suppression

Sleep disturbances

Illnesses

Nagging wear and tear injuries

During periods of training, this level of fatigue is NECESSARY for the body to be stimulated to adapt. This means the decrement in performance should be expected as it indicates the body is being PUSHED to improve.

During periods of competition, this level of fatigue is DISADVANTAGEOUS as it masks the improvements made by the body during previous bouts of hard training. During competition periods, training should function as a means to MAINTAIN adaptations rather to stimulate further improvements (2).

During this time, the goal of the athlete should be to MANAGE fatigue experienced during periods of high voluminous play- such as weekly practices, games, tournaments, and maintenance lifting sessions. During this period, recovery must be PRIORITIZED to help ensure the body is ready to showcase in sport where it matters most (1).

Prioritizing Recovery

In order to drive the adaptation process during training and help reduce fatigue during competition, recovery must be prioritized.

Recovery can be defined by two modalities: Passive and Active

Passive modalities are those that assist in the recovery in the LONG TERM

These include SLEEP, NUTRITION, HYDRATION, and ACUTE STRESS MANAGEMENT

Active modalities are those that assist in recovery in the SHORT TERM

These can include modalities such as: ice baths, compression garments, low-intensity exercise protocol, nutritional supplements, cryotherapy, massage, stretching, cupping, and neuromuscular stimulation. (1,4)

Before we dive into the TIME AND PLACE for these modalities, lets identify what each modality is:

PASSIVE RECOVERY MODALITIES

(1) SUFFICIENT SLEEP

Chronic sleep deprivation results in a decrease in performance in almost ALL parameters: aerobic, anaerobic, and mental capacity

Sufficient sleep has individual variation but the normal ranges are from 6-8hrs / night → with more sleep to be prioritized around competitions to consider the additional psychological stressors experienced

There is no amount of food, supplements, performance-enhancing drugs, or any other factors that can make up for lack of sleep (1,4)

(2) NUTRITION INTERVENTION

The second most powerful and practical alleviators of fatigue is nutrition.

Specifically the number of CALORIES an athlete consumes (3,5)

A hyper-caloric state has a profound effect on alleviating fatigue from training as most of this fatigue experienced can be explained due to substrate depletion and energy balance

This is ESPECIALLY true for athletes experiencing non-planned weight loss during training and competition periods (3)

MACRONUTRIENTS matter next, where a large part of an increase in calories consumed by the athlete should come from CARBOHYDRATES.

This is because Carbohydrate are the primary energy substrate for virtually all sporting and exercise activities (3)

Athletes who do not replenish lost glycogen stores after intense or voluminous exercise are subject to (3):

Decreases in exercise and sport performance

Decreased recoverability (and therefore adaptability)

Hypoglycemia

Decreases in cognitive abilities

Higher rates of protein degradation

Athletes who do not replenish lost carbohydrate stores, who do not take in carbohydrate amounts matched to activity levels, or just eat a relatively low amount of carbohydrates show DECREASES in acute and chronic sport performance (3).

The next macronutrient to be prioritized is PROTEIN.

Adequate protein consumption is a major component of managing microtrauma

In sport and overload training (necessary for adaptation) results in the accumulation of microtrauma in muscles, bones, and connective tissue.

Athletes generally need more protein than non- athletes (3) due to their

Increase in working muscle mass

overall increase in metabolic demand

Higher need of reparation of tissue damage

**It should be noted even if the athlete's focus is not skeletal muscle hypertrophy, increases rates of protein turnover is HIGHER in athletes

After total calories and macronutrient ratio are accounted for, timing should be prioritized next. Particularly the timing of carbohydrate intake AROUND training to help ensure the athlete has adequate fuel for performance AND enough substrate for repletion after training. This can be prioritized via intra-workout fluid, carbohydrate, + protein intake (3,4)

During hard and long training sessions, consumption of fluids + protein + carbohydrates has been shown to have IMMEDIATE positive effects on performance as well as on the PERCEPTION of fatigue experienced during exercise

This type of nutrition supplementation is a MUST for high performance athletes during long (>1-2hrs) competition and training sessions (3)

It is important to understand that protein will NOT have the same immediate effect on the perception of fatigue and elevation of blood glucose levels as does carbohydrates (3,4)……meaning drinking BCAAs is NOT ENOUGH!!!

However, protein will help ensure protein turnover rates favor synthesis rather than degradation- aiding in enhanced recovery and decreased injury rates.

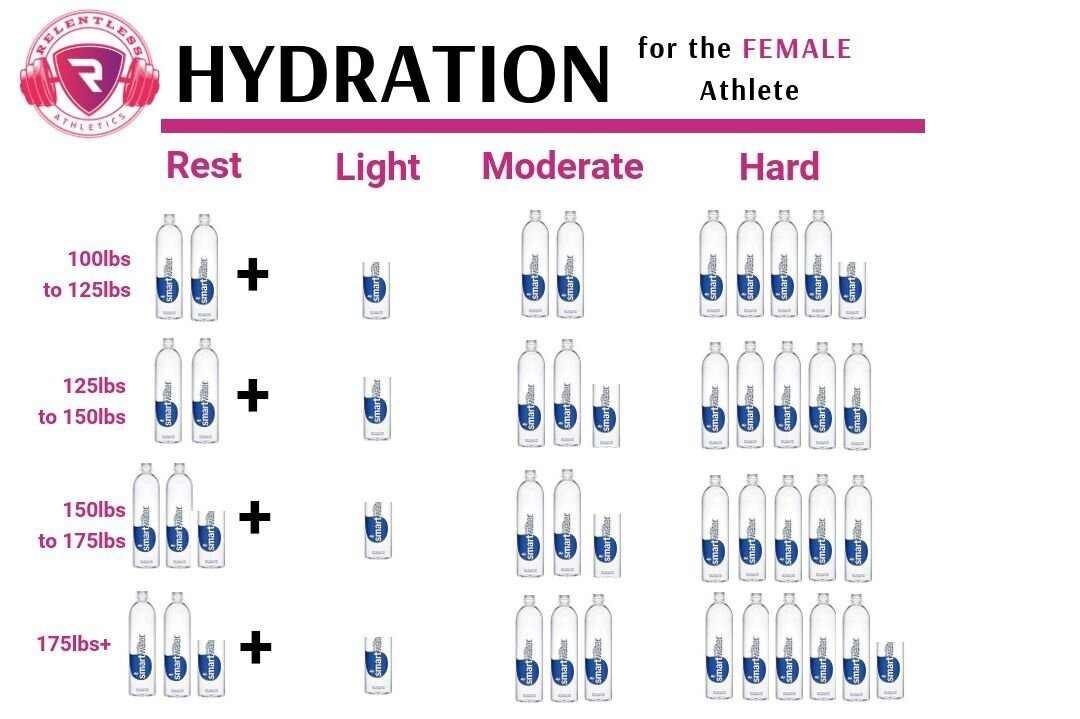

The last nutritional intervention to be prioritized is hydration.

Athletes who are previously dehydrated can have detrimental subsequent performance outcomes. Thus, rehydration following training sessions is essential to help ensure blood volume maintains high allowing for nutrient re-uptake and metabolic removal at the working tissues. (4)

For more assistance in learning how much water your athlete needs, check out our personalized nutrition templates

(3) ACUTE relaxation & FULL recovery days

When considering fatigue management, it is important for athletes to first consider if an outside intervention is even necessary OR if there has been insufficient time to recover limiting subsequent training or competition performance.

TIME is a predominant rate limiting factor in recovery. (1,4,5)

Given adequate time, most female athletes WILL recover from exercise induced stress without any need for additional intervention, This is because the body has a vast ability to restore muscle glycogen and REPAIR muscle damage given other passive modalities such as sleep, nutrition, and hydration are established.

Before an athlete considers if an ACUTE recovery intervention is needed, she must ensure she as appropriately planned her training and rest time along with a good routine of sleep, nutrition, and hydration. Overall LONG TERM recovery methods have a greater effect on adaptation and performance outcomes than short term modalities.

Once passive modalities are well-established, now lets take a look at ACTIVE MODALITIES

ACTIVE RECOVERY MODALITIES

(1) COLD THERAPY

The use of cold water immersion, ice baths, or cryotherapy has been an extremely popular post exercise recovery practice for many years. This type of therapy can be beneficial as it helps an athlete recover through VASOCONSTRICTION- or restricted blood flow to the affected area of the body. Through the restriction of blood flow, there is a DECREASE in inflammation and the PERCEPTION of pain and fatigue. LESS inflammation means FASTER recovery time. (1,4)

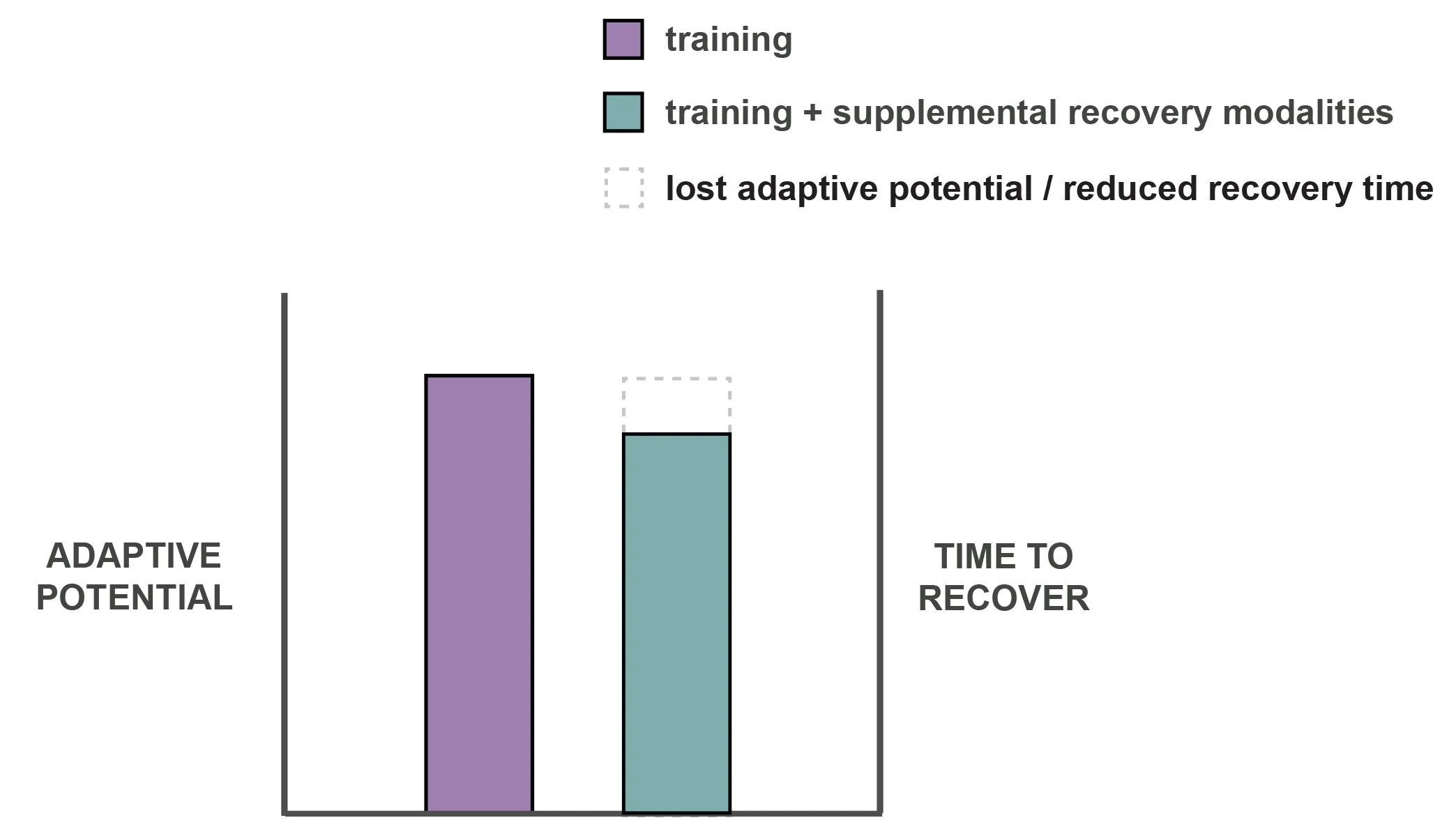

HOWEVER, this reduction in recovery time comes at a cost.

Inflammation is important in the body’s ability to ADAPT to exercise induced muscle damage.. Repression of the acute inflammatory response can therefore be DETRIMENTAL as inflammation is an INTEGRAL part of the ADAPTATION and reparation process (1)

This means the application of cold therapy can come at an expense to the adaptive potential of an athlete. Thus, using this modality during training phases when the goal to ADAT and improve seems inappropriate. Meanwhile, the utility of this modality during competition periods when the goal is to reduce fatigue and maintain high performance is warranted.

(2) HEAT THERAPY

Heat therapy interventions is the OPPOSITE of cold therapy as HEAT imposes VASODILATION or increased blood flow to the affected area. More blood flow MEANS an increase in nutrient update and waste removal. While this concept seems regenerative, research has shown ZERO benefit to exercise performance.

This could be due in part to the lack of evidence showing BLOOD LACTATE as detrimental to recovery despite previous suppositions. Overall, the utility of heat therapy seems to be lacking in any recovery protocol. (4)

(3) CONTRAST THERAPY

With this modality, an athlete alternates between cold and heat therapy. This induces VASOCONSTRICTION followed by VASODILATION. Through this application, an athlete can experience a reduction in inflammation, swelling and the perception of pain. Utilization of contrast therapy can be beneficial for an athlete who needs to FEEL better so she can PLAY better.

However, the reduction in inflammation and increase in recovery time comes at a cost in terms of decreased adaptive potential post training. (1)

(4) MASSAGE

Massage is a popular post exercise practice thought to decrease swelling & pain, increase blood flow and blood lactate removal, enhance healing, and alleviating DOMS. This modality can be performed via massage therapy or self-myofascial release (foam rolling).

Unfortunately massage is NOT well evidenced to be an effective recovery method apart from the perceived benefits of decreased tightness or muscle soreness. Although increased post-exercise muscle blood flow may help increase blood lactate removal, research indicates massage does NOT increase muscle blood flow nor the rate of blood lactate removal after exercise (1).

Even more, research has found there to be NO DIFFERENCE in post-exercise strength recovery after a bout of massage therapy, indicating there is NOT an increase in recovery (1). However, massage has been shown to help reduce the PERCEPTION of soreness. This means massage can HELP females FEEL better- but this modality lacks sufficient evidence that it enhances recovery beyond perception. (1,4)

(5) STRETCHING

Stretching has long been a common post exercise modality utilized to help enhance recovery time. The primary benefit of stretching has been believed to help increase range of motion and reduce subsequent muscular stiffness and soreness.

Unfortunately, there is very LITTLE evidence to support stretching as a beneficial recovery modality. In fact, a comprehensive review in 2006 cited there to be “no benefit for stretching as a recovery modality” (1).

In fact, as stretching functions to RESTRICT blood flow, it may function to decrease the rate of inter-muscular nutrient replenishment and waste removal. Even more, stretching may EXACERBATE muscular damage created from high intensity exercise (1) .

Meaning post exercise stretching can INCREASE the time needed for recovery and is thus NOT a beneficial modality for enhancing recovery.

(6) COMPRESSION GARMENTS

Compression garments are designed to improve venous blood return through the application of graduated compression to the limbs, potentially accelerating the removal of muscle metabolites associated with performance. Even more, the compression may also reduce the intramuscular space and support muscle structure, limiting the inflammatory response and reducing subsequent muscle soreness (4).

However, to date, only a SMALL number of studies (1,4) have indicated any real positive effect of this intervention in improving recovery time and subsequent performance bouts.

Some positive scientific evidence reveals compression garments CAN provide an athlete with a simple intervention that appears to have no NEGATIVE effect on either subsequent performance or adaptation. However compared to other modalities such as cold or contrast therapy, compression garments provide no superior benefit to recovery rate.

Therefore, more investigations need to be performed on the long term effects on compression garments and adaptive processes after training.

(7) ACTIVE RECOVERY

Active recovery modalities are common practices among athletes as a means to maintain blood flow through low to moderate intensity exercise post training or competition. The goal of this intervention is to aid in the removal of several metabolites such as blood lactate from in and around the muscle (4). While this effect or removing blood lactate is well established, lactate removal does not actually appear to be a valid indicator of recovery quality (1)

Some studies indicate performing active recovery as a separate session within 24 hours at moderate intensities may further assist in the clearance of metabolites and enhance recovery (1,4) Even more, the performance of low impact activities such as swimming act to provide an additional benefit as hydrostatic pressure from the water can enhance venous return and blood flow.

Most research indicates active recovery sessions may be most beneficial when performed between two intense sessions that are closely scheduled (<1 hr between) (1). This could be because there is insufficient time to return to homeostasis via passive modalities alone. However, it is important to understand that active recovery may be detrimental to rapid glycogen re-synthesis if proper nutrition is not accompanied with the modality.

(8) NSAIDS

Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) are a popular modality used by athletes to help reduce muscular damage , inflammation, and the perception of pain. However, despite their common use, there is limited evidence that NSAIDs aid recovery.

Instead, long term NSAIDs use has been associated with several negative health consequences. Although brief use of NSAIDs may be beneficial for short term recovery leading up to an important competition day, repeated use of NSAIDs over extended periods of time can have detrimental effects on muscle repair and adaptation to training. As such, the potential for adverse outcomes is too large to consider NSAIDs as an appropriate modality for recovery in female athletes (1,4)

MATCHING YOUR TRAINING GOAL WITH YOUR RECOVERY PRACTICE

During the time away from competition (off season and pre-season), stress should be introduced through training to elicit a SPECIFIC adaptation. During this period, passive modalities should be prioritized to help enhance an athlete’s ability to recovery and ADAPT from hard training.

During the off season and pre-season, an athlete should be following a well planned accumulation phase that functions to overload the athlete to function UNDER fatigue and increase her work capacity or fitness (2,4). These accumulation periods should only be performed a few days at a time and be followed by recovery periods to allow for sufficient adaptation from training (see ARTICLE HERE)

During these training periods, if acute recovery modalities are used chronically, these interventions have the potential to LIMIT the magnitude of subsequent adaptations (1,2,4) For this reason, it is suggested that female athletes avoid the use of active recovery interventions during these training phases when adaptation to training rather than short term performance is the GOAL.

During the season, the athlete’s goal should shift to performance and maintenance of fitness adaptations. During this period, the introduction of ACUTE recovery modalities can be utilized to help decrease fatigue and improve athletic performance (1). However it must be noted that the use of these modalities should follow a dose-response approach appropriate to the INDIVIDUAL as ALL athletes male or female respond DIFFERENTLY to these modalities.

When deciding which modality to utilize, it is important to emphasize the priority of establishing passive modalities first. There is no active modality that can replicate the long term recoverability provided by sleep, nutrition, and well timed rest days.

After those modalities are well established, other acute modalities should be chosen based on the athletes GOAL.

For instance, if an athlete needs to perform high on back to back days, modalities that can help reduce inflammation and the perception of pain may be beneficial.

IN SUMMARY

Fatigue is a necessary response to stress that helps athlete’s ADAPT and improve their performance. Fatigue also acts to MASK fitness and overtime will result in a decrement in performance.

The balance between recovery and fatigue is necessary to help enhance adaptive processes, improve performance, and reduce injury risks

However, the types of modalities utilized should be chosen based on the athlete’s GOAL and the time of her training and competition periods.

Although cryotherapy and massage sound sexy- research clearly indicates there is no replacement for SLEEP, NUTRITION, and STRESS management via rest days.

Outside of these modalities, active modalities can be utilized, however with consideration to the COST of potential reduction in adaptive potential to training

REFERENCES

Barnett, Anthony. “Using Recovery Modalities between Training Sessions in Elite Athletes.” Sports Medicine, vol. 36, no. 9, 2006, pp. 781–796., doi:10.2165/00007256-200636090-00005.

“Fatigue, Overreaching, and Overtraining .” Integrated Periodization in Sports Training Et Athletic Development: Combining Training Methodology, Sports Psychology, and Nutrition to Optimize Performance, by Tudor O. Bompa, Meyer Et Meyer Sport (UK) Ltd, 2018, pp. 154–173.

Hausswirth, Christophe, and Yann Le Meur. “Physiological and Nutritional Aspects of Post-Exercise Recovery.” Sports Medicine, vol. 41, no. 10, 2011, pp. 861–882., doi:10.2165/11593180-000000000-00000.

“Recovery Practices to Optimize Training Adaptation and Performance .” Strength and Conditioning for Female Athletes, by Keith Barker and Debby Sargent, The Crowood Press, 2018, pp. 153–170.

Skorski, Sabrina, et al. “The Temporal Relationship Between Exercise, Recovery Processes, and Changes in Performance.” International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, vol. 14, no. 8, 2019, pp. 1015–1021., doi:10.1123/ijspp.2018-0668.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Emily holds a M.S. in Exercise Physiology from Temple University and a B.S. in Biological Sciences from Drexel University. Through this education, Emily values her ability to coach athletes with a perspective that is grounded in biomechanics and human physiology. Outside of the classroom, Emily has experience coaching and programming at the Division I Collegiate Level working as an assistant strength coach for an internship with Temple University’s Women’s Rugby team.

In addition, Emily holds her USAW Sport Performance certification and values her ability to coach athletes using “Olympic” Weightlifting. Emily is extremely passionate about the sport of Weightlifting, not only for the competitive nature of the sport, but also for the application of the lifts as a tool in the strength field. Through these lifts, Emily has been able to develop athletes that range from grade school athletes to nationally ranked athletes in sports such as lacrosse, field hockey, and weightlifting.

Emily is also an adjunct at Temple University, instructing a course on the development of female athletes.